World Wide Web

Location: Ranaghat Posted on: 2/8/2026 7:46:10 AM

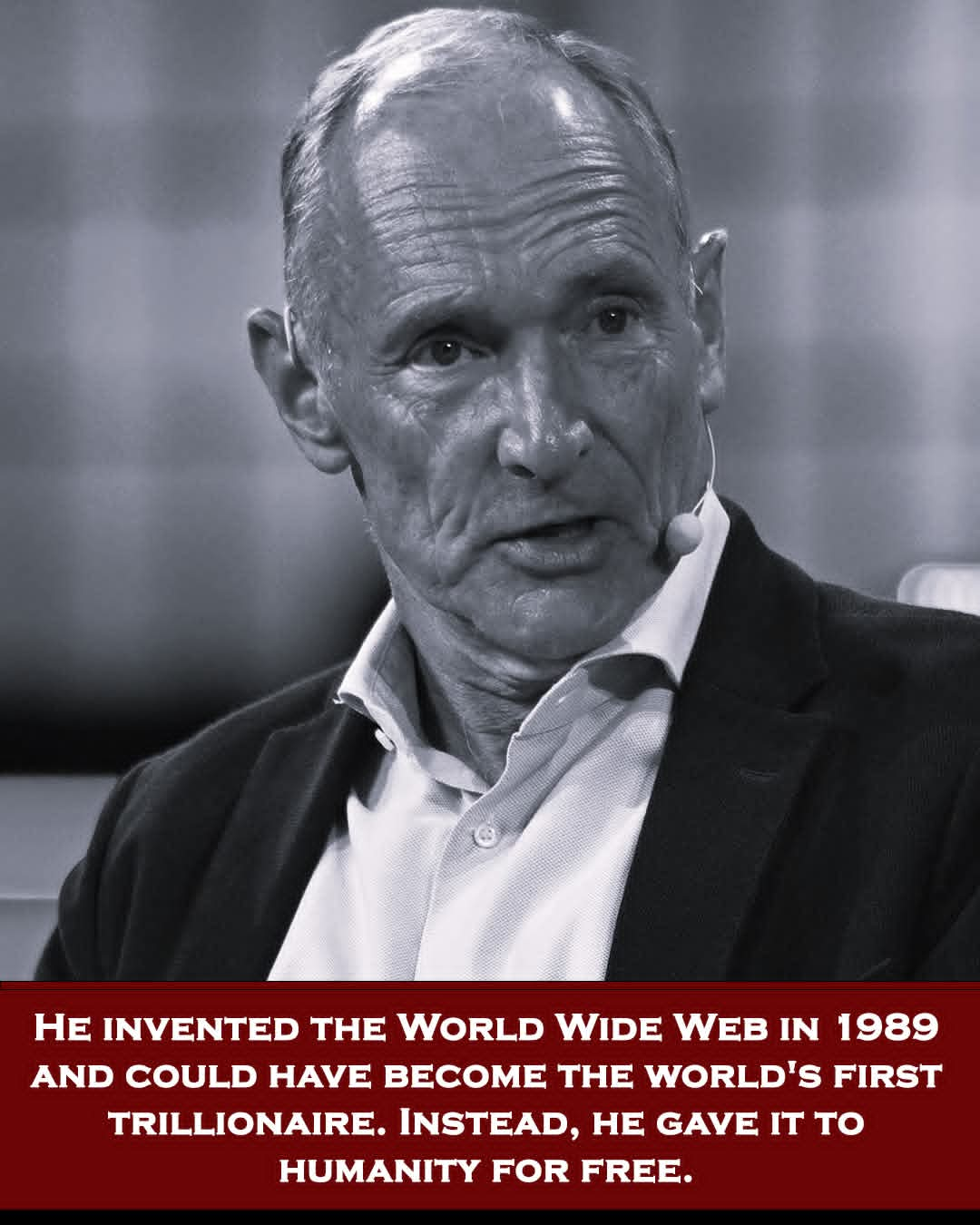

He invented the World Wide Web in 1989 and could have become the world's first trillionaire. Instead, he gave it to humanity for free. In March 1989, a 33-year-old software engineer named Tim Berners-Lee submitted a proposal to his boss at CERN, the European physics research center in Switzerland. The proposal described a revolutionary idea: a system where scientists could share information across different computers anywhere in the world, instantly, by clicking on interconnected links. His boss wrote on the proposal: "Vague, but exciting." Then he filed it away and did nothing. Tim had identified a problem that was driving researchers at CERN insane. Thousands of scientists from dozens of countries were working on particle physics experiments, generating massive amounts of data. But every research group used different computer systems, different software, different formats. If you wanted information from a colleague's computer, you had to know what system they used, learn their specific commands, and often physically go to their office. Sharing knowledge—the fundamental purpose of scientific research—had become absurdly complicated. Tim saw what others didn't: the solution wasn't better computers or faster networks. The solution was a better way to organize and connect information. He imagined a "web" of interconnected documents where you could jump from one piece of information to another just by clicking on links. Information wouldn't live in isolated silos anymore—it would be part of a vast, interconnected network accessible to anyone. It sounds obvious now. In 1989, it was revolutionary. But nobody would fund it. His boss thought it was interesting but not a priority. CERN's mandate was particle physics, not information systems. If Tim wanted to build his "World Wide Web," he'd have to do it in his spare time. So he did. Working nights and weekends on a NeXT computer in his small office, Tim started writing code. He needed to invent several things that didn't exist yet: HTML (HyperText Markup Language) - a way to format documents with embedded links HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) - a method for transferring those documents across networks URLs (Uniform Resource Locators) - addresses for finding specific documents The first web browser - software to view and navigate these documents The first web server - a system to host and share documents He was essentially inventing the entire infrastructure of the modern internet by himself. By late 1990, Tim had a working prototype. He could create pages with text and links, host them on a server, and view them through his browser. He showed it to colleagues at CERN. Some were intrigued. Most didn't see the point. On August 6, 1991, Tim Berners-Lee posted the first website to a public network. It was a simple page explaining what the World Wide Web was and how to use it. Nobody noticed. For months, Tim's creation sat virtually unused. He would visit internet forums and bulletin boards, gently suggesting people try this new "web" thing. Most ignored him. Then, slowly, a few computer scientists at other research institutions began experimenting with it. They built their own web servers. They created their own pages. By 1993, there were about 600 websites in the world. That's when things changed. Marc Andreessen, a student at the University of Illinois, created Mosaic—a web browser with a graphical interface that made the web accessible to non-technical users. Suddenly, anyone could use Tim's invention. Websites exploded into the thousands, then hundreds of thousands. By 1994, businesses realized something extraordinary: this "web" thing could change commerce, communication, everything. Companies started racing to establish web presences. Investors poured money into internet startups. And that's when Tim Berners-Lee made a decision that would shape human history. CERN approached him with a question: Should they patent the World Wide Web technologies? Tim could have said yes. If he and CERN had patented HTML, HTTP, and URLs—the fundamental building blocks of the web—they could have charged licensing fees to every website, every browser, every internet company. Think about that. Every website that's ever existed would have paid Tim Berners-Lee a fee. Google, Amazon, Facebook, every streaming service, every online bank, every digital news outlet—all of them built on technology Tim invented. He would have become incomprehensibly wealthy. Richer than Gates, richer than Bezos, richer than anyone in human history. In April 1993, CERN made the decision public: the World Wide Web would be free for anyone to use, forever. No patents. No licensing fees. No restrictions. Tim Berners-Lee gave away the most valuable invention of the late 20th century. Why? In interviews, Tim has always been clear: "This is for everyone." He believed that knowledge should be accessible. He believed that the web would only reach its full potential if it was open and free. He believed that putting up barriers—making people pay, restricting access, controlling who could participate—would destroy the very thing that made the web powerful. So he let it go. The internet boom happened without him getting rich from it. The dot-com millionaires and billionaires built their fortunes on infrastructure Tim created and gave away. Jeff Bezos built Amazon on the web. Larry Page and Sergey Brin built Google. Mark Zuckerberg built Facebook. All of them became billionaires using technology Tim invented and refused to patent. Tim Berners-Lee became a professor. He founded the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) to maintain web standards. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. He won awards and honorary degrees. But he never became wealthy from his invention. Today, more than 30 years later, there are over 1.9 billion websites. The global internet economy is worth trillions of dollars. Entire industries exist only because Tim Berners-Lee invented the web—and then gave it away. And Tim? He's spent the last three decades fighting to keep the web open and free. He's advocated against government censorship of the internet. He's pushed back against monopolistic tech companies trying to control web standards. He's launched initiatives to bring internet access to developing countries. He's warned about threats to net neutrality. In 2019, he launched a "Contract for the Web"—a set of principles asking governments and companies to keep the internet open, accessible, and free from abuse. Because the thing Tim understands—that many internet billionaires seem to forget—is that the web's power comes from being open to everyone. When people ask him if he regrets not patenting his invention, Tim gives a simple answer: "If I had patented it, it wouldn't be the web." He's right. If accessing the web required paying licensing fees, if building websites required permission, if the fundamental protocols of the internet were owned by a corporation, the explosive growth that created the modern digital world would never have happened. The web succeeded precisely because Tim gave it away. There's a photo of Tim from 2012, at the London Olympics opening ceremony. He sat at a NeXT computer—the same model he used to invent the web—while a message appeared in lights above the stadium: "This is for everyone." That's his legacy. Not billions of dollars. Not a corporate empire. Just those four words. He invented something that changed human civilization. He could have owned it, controlled it, become impossibly wealthy from it. Instead, he gave it to all of us. In 1989, he had an idea for connecting information. In 1993, he had a choice about who would benefit from that idea. He chose everyone. And that's why you're reading this right now.